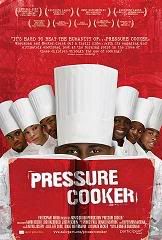

Time to mix things up a bit: Jennifer Grausman and Mark Becker, co-directors of the documentary Pressure Cooker, opening today in Los Angeles, speak with Write On! about their experience. In Pressure Cooker, three seniors at Philadelphia’s Frankford High School find an unlikely champion in Culinary Arts teacher Wilma Stephenson, who helps them earn scholarships to college through her brutal culinary boot camp. Since producing and directing Pressure Cooker, Grausman co-produced Eric Mendelsohn’s narrative film, Three Backyards. Previously she produced six narrative short films and worked in film production in New York City. Becker produces, directs, shoots, and edits documentaries in New York. Before directing and editing Pressure Cooker, Becker made the acclaimed Romantico, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival.

How did Pressure Cooker come about? How did you each get involved?

JG: I had heard about Wilma Stephenson, who runs a culinary arts class in a public high school in North East Philadelphia. She spends every year training her students to compete for culinary arts scholarships, and they are always the best prepared in Philadelphia.

I went down to Philadelphia to meet her and we talked for three hours. She was so passionate about teaching and her love for her students was so palpable, yet at the same time she had a great sense of humor and was extraordinarily charismatic. In short she seemed like a character with real depth. Wilma also told us about some of her students, and it felt like there was a story there in her classroom that needed to be told.

So we began filming at Frankford High School on the first day of school in September 2006 and stayed through graduation in June 2007.

MB: When Jen called me about Pressure Cooker, I was concerned that I wouldn’t want to be involved because it sounded like a film about a good person doing good things for good people, which wouldn’t be my cup of tea. But she showed me some initial footage she had shot, and I was blown away by the character of Wilma Stephenson (the teacher at the center of the film). Wilma just jumps off the screen. She is complicated and irreverent and she will say anything—in her charmingly blunt manner—to her kids. She just has this amazing presence.

Why documentary filmmaking?

MB: I used to edit Super8 home movies with my father using a viewer, splicer and splicing tape. We would record narration and add music to our family vacation videos. I am no longer a big fan of narration.

The other answer is that I just love the process. During production, it feels like a privilege to spend time with people you wouldn’t ordinarily meet, inside their universe. I enjoy the detective work during production as you uncover themes and narrative. And during post, my interest is in telling subtle stories by playing with the energies inherent in different kinds of scenes, and working with images and sound design to evoke ideas, memories, truths, etc.

JG: Documentary filmmaking allows you to enter worlds you might never have knew existed, and then challenges you to honestly share those with an audience. Having a narrative film background, all of this was new to me, but ultimately, documentary for me it is all about a good story, just like fiction films.

How is documentary similar to narrative filmmaking? How are they different?

JG: Documentary production is quite different from narrative filmmaking. I love being able to work with a small crew with only a few pieces of equipment. The mobility you have in documentary filmmaking is refreshing when you are used to working with a 30-person crew and trucks full of lights and equipment. The spontaneity necessary is both a blessing and a curse, but I personally learned how to work with what you have and to relinquish preconceived notions of what you thought the film was about when you began the process.

MB: With regard to making documentaries, you are working with the lives of real people as narrative material for a larger story. And I feel duty bound to honestly represent what I have witnessed and experienced. Both production and editing are manipulative processes where you are influencing and coloring what comes across to the viewer about your film subjects—through your cuts, through the structure of the film, through your tonal choices. So while I see myself as an interpreter, I am aspiring to a larger truthfulness as well. When Wilma Stephenson or one of the kids from Pressure Cooker sees the film, I would like them—the film subjects—to feel like indeed this was their experience represented on the screen.

Is a documentary actually written? If yes, how so?

JG: A verité documentary like Pressure Cooker is mostly written in the editing room, though of course a very rough draft is formulated while shooting. Mark and I spent a long time figuring out a seamless structure that would draw the viewers into the movie. We tried above all to stay away from exposition and let the audience be detectives, making the connections between scenes and characters. In Pressure Cooker, we never wanted context or statistics to take away from the characters and the action of the documentary.

MB: On each film that I have directed or edited I work within the confines of story. I am taking all the elements—scenes, images, sound design, music—and from them constructing a narrative. In the case of Pressure Cooker, all the elements of a traditional fiction film unfolded during production: There were complex empathetic characters (Erica, Dudley, Fatoumata), difficulties to overcome (complications at home, Wilma’s intense classroom), an overt goal (to achieve scholarships to escape the status quo of Northeast Philly), and a powerful subtext (as a surrogate family forms in the classroom). I don’t really feel the need to call it writing per se: It’s nonfiction storytelling.

What was the greatest challenge in making Pressure Cooker?

JG and MB: The biggest challenge in making Pressure Cooker was navigating the process with Wilma Stephenson. Although she initially agreed to the documentary and allowed us to film in her classroom, there were several points during the year where she almost changed her mind. Wilma’s first priority is her students, and during stressful times, she wanted to avoid any distractions and be able to focus on them. We were already so invested in the project and our characters, that the prospect of being shut out of the kitchen (which did happen on several occasions) was frightening. Luckily, we were able to convince her to let us come back each time. In addition, (as she readily admits) she treated us like her students in the film, although I think we often got yelled at more than the kids. Then again that helped us become closer to the kids, as we were all in the same boat.

Another challenge was trying to make appointments with seniors in high school—we were stood up on more than one occasion, but became very talented in tracking them down as the year went on.

What was your greatest experience with the film?

MB: It was a true privilege to spend time with Fatoumata, Erica, and Dudley. Of course their ambition and drive was inspiring—as high school seniors trying to rise above the fray; but more that, I was moved by their candor and generosity during the filmmaking process. It is intimacy and access that so often makes for an affecting documentary, and they granted us this. When I see them at screenings, I feel so lucky to have spent time with them.

JG: Seeing the finished film with Wilma and all of the kids for the first time was an amazing and overwhelming experience. They first saw it with an audience of 1,200 public high school students in Los Angeles when we premiered at the Los Angeles Film Festival last June. I was so nervous to see their reactions, as well as that of an audience, but it went better than I could have ever hoped.

The audience erupted into laughter, cheers, and tears. They embraced Wilma and the kids—asking for autographs, begging Wilma to come and teach at their schools in LA, asking Erica for advice, and telling us that no one ever tells their story. It was incredibly gratifying.

Any advice for writers and other creative professionals who want to get their work seen/noticed?

JG: Although it’s early in my career, I feel that it’s important to keep writing, to keep plugging away at your craft. And to find a few people you trust to give you honest feedback. Once you have a story you have to tell, you will find a way to make it happen.

MB: I certainly don’t feel like a sage in this regard, but I do strongly believe in telling stories that have real personal resonance with you, rather than guiding your vision by what you think people want.

What’s next for each of you?

JG: I am currently producing two narrative features—both are in early stages of development—and working on a screenplay. I’m also researching future documentaries.

MB: I can’t wait to make another movie. I’m not sure what it is yet. I also work as an editor, and I am currently editing a beautiful documentary about a family circus (of many generations) that travels from town to town in rural Mexico.

Tags: Author Q&A Culinary Arts Jennifer Grausman Los Angeles Film Festival Mark Becker Pressure Cooker Support Wilma Stephenson Write On! Writing

Comments are closed.

[…] Jennifer Graussman & Mark Becker, Co-Directors, Pressure Cooker […]

[…] Jennifer Graussman & Mark Becker, Co-Directors, Pressure Cooker […]

[…] July 3: Pressure Cooker, directed by Mark Becker and Jennifer Grausman, will be playing at 7:30 pm at MoMA in New York. The documentary is about Philadelphia […]